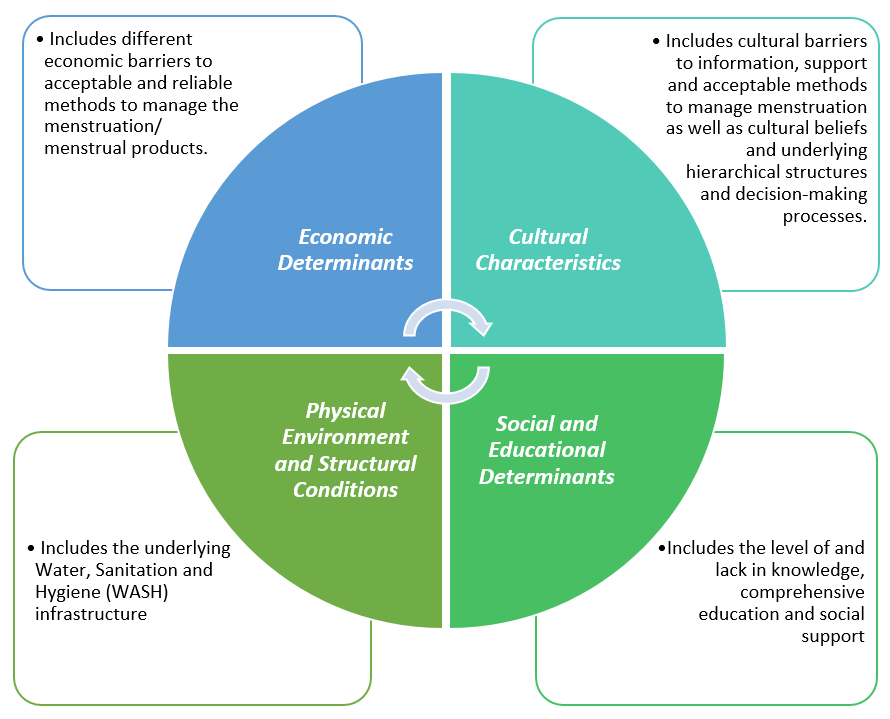

Often and in ‘mainstream media’, menstrual poverty is equated to a menstruator’s lack of menstrual products. However, this equation does not paint the full picture as many different factors apart from material deprivation and economic determinants may leave a menstruator deprived.

What is menstrual poverty and how does it impact menstruators?

Menstrual poverty, also called period poverty, is understood as the range of interconnected deprivation which menstruators face.[1] These relate to four categories:

Physical and material deprivation

Economic determinants, such as the availability and affordability of acceptable and reliable methods to manage menstruation (aka menstrual products), influence the level of menstrual poverty. For example, especially in resource-poor settings, menstrual products might be scarce or not available at all – neither in local shops nor distributed by humanitarian organisations or charities. Furthermore, if menstrual products are available, a menstruator might not have the financial means to purchase the preferred (or any) menstrual product. Having to prioritise other goods, such as food, over menstrual products is one reason for this and in this case directly links menstrual poverty and food insecurity.

Additionally, the physical environment and structural conditions surrounding a menstruator impact the level of menstrual poverty. This includes the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, ranging from clean water to disposal facilities and waste management, safe spaces that guarantee privacy (e.g., private, lockable latrines or toilet facilities), and influencing and changing menstruation management behaviour.[2] The existing WASH infrastructure may be lacking in quality in terms of being only partly implemented (or not at all) and might be inaccessible. These conditions directly influence the personal menstruation management, the reproductive health (e.g., urinary or reproductive tract infections), as well as the privacy and (perceived) dignity of a menstruator.

Psychosocial deprivation

The level of and/or lack of knowledge about the reproductive system and health as well as menstruation management techniques and the accuracy of myths around menstruation may negatively impact the physical and mental health of a menstruator. Education in general is a social determinant of health and a lack of education and social support offered in schools by teachers, in private and communities by parents, guardians, family members, friends, neighbours, etc., negatively impacts the reproductive health outcomes of menstruators.

Additionally, underlying cultural characteristics impact the level of menstrual poverty. Cultural beliefs in particular, as well as the general hierarchical structure of a community as a whole or even of a family, influence how menstruators learn about and experience menstruation. If, for example, the head of a family is responsible for managing the income and budgeting the money, menstruators may be left without means to purchase adequate menstrual products. Additionally, cultural barriers to accessing information, asking for support or using a specific menstrual product may exist and deprive menstruators in their daily life. For example, menstruators are unlikely to use a tampon or a cup if they grew up in a culture that values virginity and sees tampons or cups as a threat to this. Or menstruators who grew up in a culture that labels menstrual blood as toxic may not want to use reusable menstrual pads – even though these might be cost-effective and sustainable.

What can be done to tackle menstrual poverty?

Menstrual poverty is much more than just a lack of menstrual products. To tackle menstrual poverty, especially in resource-poor settings, all interconnected factors that deprive menstruators must be considered. When, for example, implementing an intervention based on the lack of availability or affordability of menstrual products, the approach should be culture-sensitive but nonetheless include health promotion that educates menstruators about menstruation management as well as reproductive health and consider the structural conditions menstruators live in.

The goal is to tackle stigma, shame, shyness, secrecy and silence around menstruation to raise awareness and advocate for change, improve the health of menstruators and their menstrual experience, decrease inequalities and make menstruators’ rights a reality. This can be achieved by following a holistic approach, considering all interconnected factors as well as teaming up with other actors and stakeholders from other sectors.

*

[1] To include all kinds of people who menstruate (e.g. transgender or intersex people) I’m using the gender-neutral term menstruator instead of referring to girls and women only.

[2] To learn more about the language around menstruation, read this article by Chella Quint on Bloody Good Period.

Featured image by Brian Otieno for DSW.