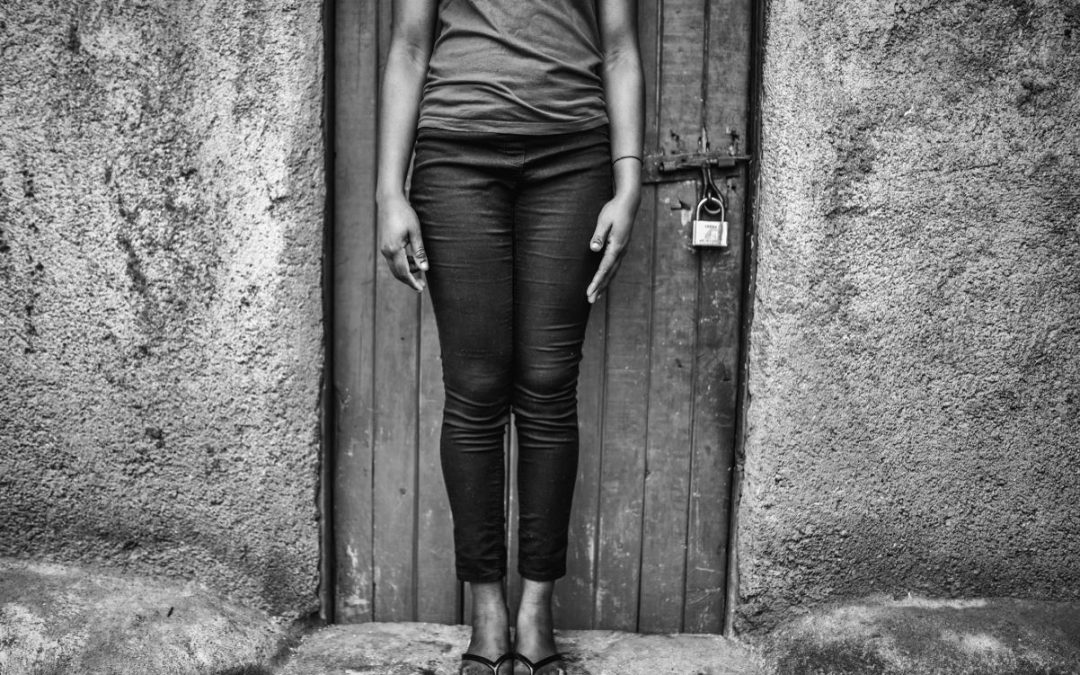

It is shocking to imaging that even in 2021, over 200 million women worldwide are affected by Female Genital mutilation (FGM). What’s even worse is the knowledge that the number of cases are actually on the rise.

According to the current World Population Report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), it has been forecasted that the number of girls and young women exposed to this devastating practice could increase from 4.1 million in 2020, to 4.6 million by 2030. Times of crisis, such as a the spread of COVID-19, also exacerbates this problem. As we have written about in the past, lockdowns and school closings during the pandemic in east Africa, have seen an increase in the number of cases of child marriage and FGM. There are multiple reasons as to why certain communities would continue this harmful practice; in many cases it is often seen there as a rite of passage to adulthood. Girls who have not gone through this painful ritual are often viewed by the community as not fit for marriage, or even for other basic social functions. Such discriminations include refusing to eat food prepared by an uncut woman, or refusing to allow uncut girls to fetch water from the same well or gather firewood with girls who have undergone FGM. This type of social ostracisation heightens the pressure on young girls to undergo the procedure.

According to UNFPA, the proportion of girls and women affected by genital mutilation is declining overall, but the absolute number of girls and women subjected to this practice is increasing due to population growth. Thankfully, opposition to this harmful practice is increasing with tremendous strides made over the past few years to end FGM and also forced marriage. Unfortunately, the current pandemic and restrictions in social contact and outreach have added an extra layer of complication in addressing this problem.

Lifelong consequences

The short- and long-term consequences of this patriarchal practice can be very severe. The short-term consequences of genital mutilation include severe pain, severe blood loss, infection and death. Many of those affected suffer lifelong trauma, psychological problems, impaired sexual sensation, infertility, and birth complications, and they are at an increased risk of stillbirth.

What DSW is doing to address this issue

Through international pressure, and our offices in east Africa, we are working hard to end this practice for good. We see it as vital that communities, and especially girls and young women, are educated about the consequences of this practice. One way we have been doing this is through our youth clubs, which have been making considerable strides in changing gender norms. Outside of the club structure, we remain committed to empowering influencers within communities so that they can actively campaign for gender equality and the removal of harmful practices such as FGM. This includes policy makers, religious leaders, teachers, as well as survivors and those at risk themselves.

DSW Project: Educate Against Female Genital Mutilation

In Tanzania, approximately 15 percent of women between the ages of 15 and 49 are victims of FGM. In rural areas, the figures are often higher, despite the practice being banned since 1998.

To help turn the tide on FGM, DSW Tanzania launched a two-year project (2018-2020) targeting 160 girls and young women in four wards: Mwandeti, Musa, Sokoni II, and Olmotonyi. The project focused on empowering these young women (14-24) who had either been victims of genital mutilation, or were at a high risk of becoming victims. Since a multidimensional, social approach is essential for the abolition of this harmful practice, the project also sought out and included parents, religious and political leaders, and local media.

Overall, more than 2,000 community members were reached via events and community dialogues involving a wide range of local stakeholders. Young women were trained as peer educators to spread knowledge on sexual reproductive health and rights, including the effects of FGM. As a step towards further empowerment and a break away from patriarchal control, the project took the initiative to provide training to women in the fields of advocacy, leadership, and business skills. This was seen as an essential component in advancing young women’s ability towards making self-determined decisions, especially in rural communities.

Additionally, all villages visited under the project committed to a joint, public pledge to abandon FGM. The project also strengthened girl’s protection systems (local level legal authorities) such as the ‘Police Gender and Children Desk’, and the ward tribunals so as to enable better responses to those in need. Both actions have advanced the legal framework for reporting unlawful FGM practices, and offer a new layer of protection for vulnerable girls and young women.

This project is just one of many initiatives that we are working on to eliminate this harmful practice once and for all. There still may be a long road ahead, but we will continue pushing for change until the work is done.

———————————————————————————————————–

Further Resources:

- Find out more about DSW Projects (and the ‘Educate Against Female Genital Mutilation’ project): https://old-en.dsw.org/projects/

- Read more about what we are doing about FGM: https://old-en.dsw.org/?s=fgm

- Information from the UN about FGM: https://www.un.org/en/observances/female-genital-mutilation-day

- Information from WHO about FGM: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2021/02/06/default-calendar/international-day-of-zero-tolerance-for-female-genital-mutilation

- Information from UNFPA about FGM Day: https://www.unfpa.org/international-day-zero-tolerance-female-genital-mutilation

- Want to get involved? Reach out to us via our social media channels! Post your comments and ideas there and we will get back to you.